I’ve been burying the lede all week, so I will try to avoid that here: on Sunday, after a couple grueling months battling colon cancer and the state of debilitation that can follow, my mother passed.

The event was, somehow, both expected and unexpected: we, her family, knew it would happen, we were given some timelines from medical professionals that proved to be annoyingly correct, but we also didn’t think it would be so sudden. I remember an idyllic day spent sledding in the park with M, my son, and his mother—an arrangement that is a topic, along with my mother’s care, of my novel-in-progress—and then getting back to the apartment, with M about to serve everyone homemade goulash (with paprika brought in by a coworker, from Hungary!), when I looked at my phone to see a series of missed calls from a number I didn’t recognize—my sister’s husband, it turns out—followed by a series of texts from my sister, updating my father and I on the group text with hyper-medical information like my mother’s oxygen level and breathing status, before delivering, without warning, the stomach-dropper: “Mom is gone,” which I still somehow hoped, childishly, might mean she had just disappeared, somehow slipped out or was taken somewhere.

I suppose, in a way, any of those could be true too. Disappeared, slipped out, taken.

And now, it’s also true, gone.

—

That was Sunday. Today I’m back in South Carolina, to help my father and family, after a couple days of agonizing decision-making (or decision-not-making).

It’s raining outside and though it’s nearly noon, I’m still in bed, at my parents’ house—I guess, technically now, my father’s. (That’s the other thing that has been hard: words. Language. Morphing possessives, shifting tenses to past, the strange tiptoe around words like “the body.” A notable phrase from the otherwise reverent funeral director, about the cemetery: “They just don’t like to receive anything past three-thirty.” Any-thing!)

Since hearing the news, I’ve been feeling a lot while also feeling unsure what, exactly, I should do next. It’s a characteristic enough place for me—feeling too much while doing too little—though the indecision that’s gripped me (if I may put it so self-seriously) since Sunday has felt somehow stronger, stickier.

Worried, I mentioned my condition to M before the trip. But she said, laughing a little, that she “hadn’t noticed a difference.”

Perhaps it’s what my sister, one of the medical professionals with the annoyingly correct timelines, might describe as a “baseline”—my baseline.

Still, I think it’s more right now. More indecision, more torpor. Although I have funereal tasks to complete, this morning’s big (in)decision has been whether—let’s see if I can say this clearly—I should schedule an optional “office hours” session over Zoom to take the place of the in-person class I’ve already cancelled and rescheduled for the end of the semester, a move that was kindly suggested by my director. In other words to go back on what I already did, but not entirely, just partway.

The worry came from asking our teaching assistant how the discussion section had gone—well enough, it seems, though the students had some questions. Which is like, of course, because it’s the beginning of the semester and suddenly there’s some shakeup.

But in the moment, I thought: Should I fix this? Should I try to fix this?

This desire to fix, and to respond, like the indecision, feels to me unhappily characteristic—what I’ve come to call, with a sort of sour affection, “my pinballing,” though maybe it’s more like whiplash, or “unloading,” as M has taken to describe it.

Switchbacking could be another term, more hikerly. A former employer termed this “zigzagging” (which, naturally, they hoped to avoid and which, inevitably, we still did often).

Whatever it is, it feels especially typical right now. (Case in point: while writing this, I texted my sister, who joins the chorus of the director, M, and previous me: Yes, right call.)

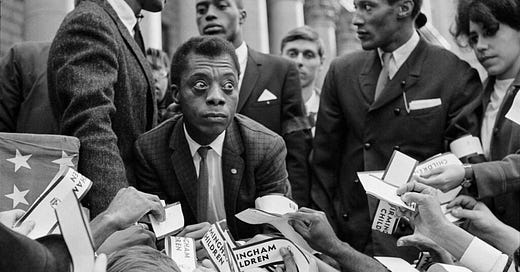

I assume this all has to do with regrets (things that could have been done differently) and lessons (things we won’t do or let happen again)—all of which stems from our mother’s care and now death. I’ve searched for years and years for relief from this second-guessing (and third-, and fourth-); the best I’ve arrived at is something akin to James Baldwin’s famous exhortation: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” That’s the part people (myself among them) usually repeat, though the next beat, less-repeated, is good too: “It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

In the opening to Mothercare, Lynne Tillman’s bracing and deeply candid 2022 book about caring for her dying mother, she writes: “I want to say about this situation: It is impossible to get it completely right.” At the end, she writes, with longing yet also the possibility of surrender: “But then there are many regrets after a parent dies.”

I find both these lines true and, in their way, consoling. (Consider I am someone for whom Kierkegaard’s “do it or do not do it—you’ll regret both” is consoling.) In today’s class, we would have discussed Lydia Davis’s “Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits,” which is so good—so practical and generous that it almost snuffs the magic—that I am always assigning it to each class I teach, usually as a kind of foundational text. And each time we read it, I notice something new, or remember something I had forgotten—that’s the joy of rereading good writing. The joy, as well as use.

Last week, in rereading it again, I noticed a line that hadn’t really hit me before: “For any problem you have, there will be an answer in the close analysis of one or more good writers.” She’s referring to craft problems, of course—in this particular instance, examining how Barbara Pym “achieves her funny moments”—but I like Davis’s optimism, that there will be an answer. We just have to look and think clearly, and in the right place. I like to think it can apply more broadly, too: that for whatever our problems, there’s some beautiful, wise text, or texts, for us. They may take some time to find, and probably more to grasp—perhaps we may even have to produce these texts ourselves—but they’re there. Waiting to help.

Even if we will one day regret it—reading, after all, takes time; writing takes time and struggle; and we all know how little time and how much struggle there already is in the world—but we’ll regret the other too, maybe more.

Like what one of Svetlana Alexievich’s interviewees, in The Unwomanly Face of War, says (about war, but still): “It’s terrible to remember. But it’s far more terrible not to remember.”

Good words to keep in mind, when working on an obituary for your parent.

As Lynne has said, paraphrasing Gramsci: “Pessimism of the mind, optimism of the will.”

James- It’s definitely far more terrible to *not* remember. Thanks for sharing.

God, the second guessing..! Its rough. I'm both amazed and not amazed you're able to write all this. It's so much to think/feel. sometimes writing feels like a release of the dam. Sorry about yr mom❤️