“The thing you get instead is better”

On avoidance, not listening a little, and going where you don’t want to go

Early on in Emmanuel Carrére’s 2014 novel The Kingdom, the French writer talks about the lines, from John 21:18, that made him a Christian:

Amen, I say to you,

when you were younger, you used to dress yourself and go where you wanted;

but when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands,

and someone else will dress you

and lead you wherever you do not want to go.

A beautiful sentiment, don’t you think?

While these lines did not convert me (nor did they, in the end, keep Carrére), they do feel resonant. Especially that last part, about being led “wherever you do not want to go.” Carrére writes that he’s attracted to the “act of abdication that can also come as an immense relief.” In short, he wants to “abandon” himself. It’s what he wants “most in the world,” he says: is to be led where he doesn’t want to go.

This idea of surrender speaks to me too (though I’m less certain about wanting to be taken where I don’t want to go; probably I would like to be led where I want to go just as much). Still, as I’ve grown older, I’ve learned the value of discomfort, of avoiding avoidance. Going where you don’t want to go, I have come to find, just might be the quickest ticket to growth, to keeping our lives from getting too staid or small. I think a lot about what the director Caveh Zahedi told the writer Christine Smallwood: “The central trope of all my films, I think, is: ‘You want this. You don’t get it. The thing you get instead is better.’ And that’s the central trope of life.”

I don’t agree that what you get is better; what you get, I believe, is what you get. Calling it “better” feels a bit self-justifying to me. (Maybe, I will concede, it’s more interesting.) But I do think we should learn to accept what we get, and perhaps think of it as better, because it is a lesson—a gift. Even if it hurts, even if it takes us to where we don’t want to go. Where we wouldn’t have even thought of or dared to go—and then there you are.

A great example of this getting something else is in Zahedi’s 1994 film I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore, maybe the work of his that I feel closest to. The film follows a thirty-something Zahedi’s attempt to bond with his estranged father by taking him on a Christmas road trip to Las Vegas where, we learn, Zahedi tries to convince the aging patriarch to take ecstasy with him. After some back and forth, the father finally relents: he’ll take it for his son, he says. Then, during the pivotal scene of father-son bonding, the camera assistant inadvertently loads an already-exposed roll of film, causing the two images, past and present, to be superimposed.

Instead of redoing it, however, Zahedi decides to roll with the mishap, to stunning effect:

The whole film serves as an example of Zahedi’s “what you get is better” ethos. In the final monologue, he explains: “At the beginning whenever anything went wrong, or went differently than what I had planned—hoped, wished, conceived, thought—[I would] get very scared, and angry. And think: Oh no, it’s not working out, it’s going to be terrible. And now, on the way back, you know, all these things happened differently than I would have planned. And I just felt like, Okay. That’s okay—or that’s good. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. And I embrace it. I accept it”—here he worries he’s going on too long, asking himself what time it is and checking his watch, before returning to the moment—“You know, I love it,” he says, then corrects himself yet again: “I’m trying to love it.”

I don’t mean to say that I am “embracing” the death of a parent, but in some ways I guess I am. It’s something I will have to accept, to come to terms with, as well as everything comes after. Not a place I would have wanted to come to, but then again here we are. What can you do?

—

I’m reminded of something else, a story I like to tell: During the pandemic, when my dog was dying, I had to carry him everywhere, to places where he didn’t want to go, such as the bath, and also to places where he wanted to go but couldn’t on his own, like the park. One afternoon at the park I was carrying him out like this when an older man stopped me. He first asked how old my dog was and I told him (seventeen) and then, maybe not hearing me the first time, he asked the same question again and I repeated my answer. Then, assuming that I was carrying my dog because he wouldn’t walk not because he couldn’t walk, the man said something I will never forget: “I think it’s beautiful when they don’t listen a little.”

I was standing with my good friend Michael that day and I remember turning to him, dumbstruck at what the man had said, which I immediately recognized as a gift. But I had no idea how great the gift really was, and how it would become something I tell myself, or try to tell myself, every time I get led somewhere I don’t want to go, that this instance of life not listening a little isn’t annoying or angering, as I am often tempted to think, but, in fact, beautiful.

—

Not long after I first received the news about my mother, I said to myself, as a kind of benediction, that we all grieve in our own ways. Naturally this—shall I call it an ideal?—was tested as soon as I saw my father again, the two of us now in this new sad era.

After answering the door to let me in, my father went right back to the couch to whatever he was watching on TV (sports? the news?) before I arrived, no hug, no consolation or understanding, just a few perfunctory if slightly haggard words, almost commands: “Meal on Wheels in the refrigerator. Or salad. Or yogurt”—his way of saying, If you’re hungry, there’s food. Get it yourself.

Sure, it was past eleven o’clock by that point, because of a delayed, then redirected flight. But in that moment, thinking of how either of M’s parents would have received her in such circumstances, or how my sometimes gruff friend Zaq had received me with a big hug, I felt disappointed, angry, and uncared for.

But, really, who was I—or any of us—to judge? To each their own. So what that his grief didn’t look like mine, or anyone else’s I could imagine.

—

And so it goes. When my mother was alive, her stubbornness would drive me up a wall. And I can tell it bothers me still, as well as my father and sister, now that she’s gone. “If only she was active, drink more water, and use more common sense,” my father texted us the other day, on the group thread, a variation on what we’ve all said, at some point over the years, back before she was even very ill. Go for a walk, see friends, take care of yourself, in other words—these small steps for self-care that we suspect could have extended and improved her life.

The self-improvement part of me says, annoyingly and rightly, to heed the lesson: take care of your body and your physical needs. But I want to think more broadly about it too—my mother’s withdrawal those last ten or so years was not unconnected, perhaps, to my family’s relentless badgering. Or, even if it was, these behaviors were also part of what made her her. And we all need to be given some space to refuse.

Maybe, really, the takeaway is this: As we each should be allowed to grieve in our own way, so shall we be let to live.

—

I received some touching responses to my last post, including a book recommendation (Healing After Loss, which looks helpful—thanks, Lisa) and too many other messages of kindness to mention here. These messages mean a lot to me. Thanks so much for sending them, and thanks too for reading and subscribing.

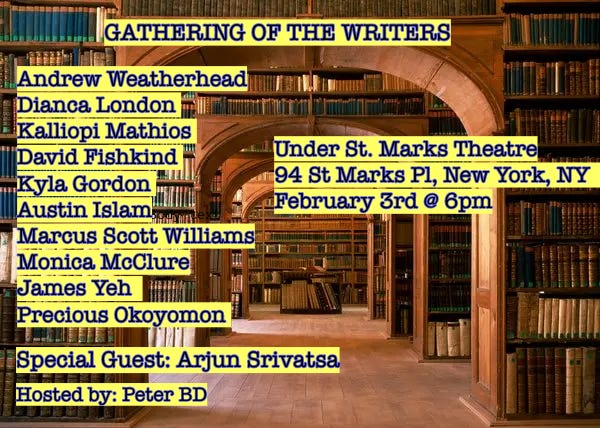

Oh, one last thing: I was invited to do a reading at my friend Peter BD’s Gathering of the Writers event in New York this Saturday, February 3. I thought it might be cathartic to do, so I said yes. I’ll probably try to read something new (and, one hopes, not too glum) from the novel I’ve been working on. Would love to see some familiar faces if you are around.

Tickets, Peter says, are pay what you want.